"My Husband Didn't Have to Die"

One day my husband, Jim, was active, athletic and enjoying life. The next day he

was gone. His death from complications of deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) was a terrible

shock to me, and six years have done little to ease the pain. The worst part is

knowing that it didn't have to happen – that if anyone had warned us that Jim was

at risk for DVT and told us how we could avoid it, he might still be here today.

Joining the campaign

I have since learned that that's the nature of DVT. It can sneak up and take you,

and you're gone. When I heard the news of David Bloom's death in 2003, it felt like

another devastating loss. In the two years since Jim had died, I had done a lot

of reading about DVT and knew how it happened. But I still was shocked that it had

taken yet another life, for no good reason. Why didn't somebody tell David he was

at risk? For that matter, why wasn't somebody telling everybody about DVT?

Soon after, I saw Melanie Bloom on Larry King Live and realized that somebody was

doing just that. I wanted to help in any way I could. When I went to the Coalition

to Prevent DVT Web site, I saw "Share your story" and typed in the story of Jim's

and my experience with DVT. If telling our story makes just one person more aware

of the symptoms of this condition, I'll be grateful.

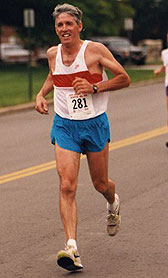

Healthy and fit

Jim had retired in 1995 and become the best "househusband" I could wish for, keeping

things running smoothly at home while I continued working as an insurance agent.

In early 2001, when he had elective knee surgery, he was a youthful 60 year old.

At 6'5" and 220 pounds, he was in excellent physical condition. He didn't smoke,

took good care of himself and loved to run. In fact, that was why he decided to

have the surgery – he said he wanted to run at least one more marathon before he

got old.

The surgery, performed on February 15, was successful and caused no apparent complications.

Afterward, the doctors didn't mention any heightened risk of developing blood clots;

they didn't prescribe blood thinners or even tell Jim to take aspirin. They did

provide a passive-exercise device for him to keep his legs moving while he recuperated

in bed, but after four weeks they said he didn't need it anymore, so he stopped

using it.

DVT strikes

On March 27, we called the doctor because Jim's leg was swollen. My husband said

he wasn't in pain, and maybe he was telling the truth – "pain" is a relative term.

But I think he was just too stoic to admit he was suffering. The doctor simply told

him to elevate the leg and place ice packs on it. When I arrived home that evening

the swelling was not nearly as bad.

Jim accompanied me to a business meeting that evening about wills and estate planning.

When the meeting ended after about an hour and a half, we walked to the car, Jim

on his crutches. Then, after we got in the car, he passed out. I drove straight

to the hospital, where right up to the emergency room door he protested that he

was fine and wanted to turn around and go home.

In the emergency room, as Jim was talking to the doctors, he got sick to his stomach.

The doctors went to put him on the table to examine him. As they lifted him, his

entire body suddenly went completely limp and turned purple from the neck down.

In a matter of seconds, my husband was gone. He never knew what had hit him – a

pulmonary embolism.

Beating my drum

The loss of my vibrant husband to DVT has changed me in many ways, especially the

way I now live my life. Although my life will never be the same, I am now empowered

to be more proactive about the health care of everyone I love, asking more questions

and doing my own research. I've learned the hard way that not all health care professionals

are as aware of DVT as they could be, and even those who do know the facts may not

communicate them to their patients.

When I meet anybody who is scheduled for surgery, I tell them to read up on DVT.

It would be wonderful if a year from now, everyone scheduled for any kind of surgery

was handed a pamphlet about DVT and had a health care professional go over it with

them. Until these actions become standard operating procedure, it's up to people

like you and me to fill the knowledge gap. We need to spread the word to everyone

at high risk for DVT: not only hospital patients, but also everyone who travels

by air, pregnant women on bed rest, and people that work in offices and call centers,

who sit for hours at a time.

The good news about DVT is that it's preventable and treatable. It's just a matter

of making everyone aware of it. I know I'm going to keep beating this drum until

everybody hears it!